|

Both “Ali” and “A Beautiful Mind” take as their subjects men who seem to control the tumult surrounding them with the sheer power of their mind. Michael Mann and Ron Howard have undertaken a study of how. The onscreen incarnations of Muhammad Ali and John Nash peer silently at the world, filtering it through their respective geniuses, and often you have your doubts about their reticence: Is Ali not speaking because he’s really a dumb jock? Is Nash’s brain freezing up in paranoid delusions? Then they talk, unleashing a trenchant wit that downsizes and remakes the world around them. Instantly we understand that there’s far more going on inside those heads than we could ever imagine. “Ali” and “A Beautiful Mind” work as biographical treatments but offer interesting and related examples of poor craftsmanship on the part of their makers.

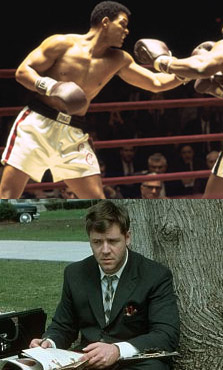

Mann’s heavily stylized “Ali” uses a highly localized point of view to give us the inside dirt on the man who most observers agree is probably the most important, symbolic, and entertaining sports celebrity in history. As the film opens, we trail Ali on a morning jog through New York, intercutting with scenes from a jazz singer performing in a smoky Harlem nightclub. The scene is without dialogue, and at first seems almost incoherent. After a minute or two, however, the images begin to form a kinetic picture of Ali’s mind. He is jogging, and thinking, and, most importantly, as he does throughout the movie, simply observing. With the jazz, the cops who trail him in a prowler, and the sights of sixties Harlem, Mann expresses a succinct and compelling vision of Ali as an individual inhabiting a distinct, volatile moment in American history. He uses this technique throughout the film, such as Ali riding the subway as a child, stopping to look at a riot, or training in Africa. Mann has created an almost Joycean narrative style, one in which an entire consciousness is made up of snatches of words, music, and images. The result, jumpy and scattershot as it is at times, can be challenging to follow, but Mann succeeds— just— in giving us a highly watchable portrait of the public man and his times.

“Ali” all but wastes Will Smith’s remarkable performance, however, because Mann’s narrative style traps the audience in a sort of no-man’s land. The point of view is limited to Ali’s, but Mann still upholds a respectful superficiality about the champ’s thoughts. Presumably this was done out of reverence for this almost legendary figure, who is still alive, but whatever the case, the movie offers scant insight into the deeper workings of Ali’s mind. There’s very little in the story that even a casual sports fan wouldn’t know. When he walks into a press conference, for example, he is stone silent until he blows into the room, at which point his mouth discharges volley after volley of hilarious provocations. This is a nice touch, actually, because immediately we understand that Ali was a showman and knew it. He enjoyed showing the world its face in a mirror, and his special talent was that the more playful he seemed, the closer to the truth he got.

But Mann shows us nothing we haven’t seen on TV. Agonizingly, although Mann’s style is suited for an intimate psychological profile, he steadfastly refuses to part the curtains. Only once, when we hear Ali’s inner monologue as he studies George Foreman at the other end of the ring, do we experience a privileged moment— and it comes at the end of the movie. Watching “Ali” is like watching an opera without a libretto, except instead of Italian we’re left trying to decipher Ali’s silence. Mann made half a movie, and without Will Smith’s cool ebullience, the film would be a catastrophic failure. Smith ably embodies Ali’s charm and dynamic intelligence if not his muscles.

Ron Howard’s narrative apparatus in “A Beautiful Mind”, on the other hand, is the very picture of clear, easy to follow competence. Though he is often guilty of ham-handed bluntness (“What is important in life?”, Nash asks late in the movie, at which point Howard immediately cuts away to a baby’s pacifier lying on a table), Howard has developed a neat, expository style that’s well suited for a less demanding biopic. Nash’s schizophrenia is handled with easy professionalism. A sickness that could be as bewildering to an audience as it was for the genius whom it afflicted is presented as cleanly as possible. In fact, the film actually feels sanest at those moments when Howard takes us through a day in Nash’s hallucinatory life.

As Mann does with “Ali”, Howard initially chooses to live or die with a specific point of view, and some of the early scenes, as when Nash gazes thoughtfully at light refracted through a glass, or cracks a wall’s worth of code for the government, work well, inspiring us with the proper wonder and amazement at Nash’s brilliance. The early scenes at Princeton are clever and funny, but don’t shy away from that tricky math stuff, which Howard (surprisingly) depicts without giving it the usual Hollywood watering-down. Howard’s mistake is that he pushes the movie away from Nash’s perspective after his illness is diagnosed, and the story drowns in mindless bourgeois respectability. As soon as Nash becomes a paranoid schizophrenic, the film frantically gropes in the dark for the reassuring firmness of family values.

Now, unquestionably, Nash’s story is intriguing because he is a genius who must learn to live a life more like those of the rest of us mere mortals. He must take out the trash, love his wife and child, and take a meaningful role in a community. Fair enough— who wouldn’t cheer at Nash’s remarkable, if mundane, domestic achievements? But Howard goes way too far, bleeding the rich potential right out of Nash’s story. When Dr. Rosen (ironically, a figment of someone else’s imagination, namely Irwin M. Fletcher’s) tells Alicia that Nash can no longer discern reality from fantasy, and a minute later Alicia isn’t quite sure if Dr. Rosen isn’t really a spy, Howard seems to be on the verge of touching on that great postmodern theme dear to so many late twentieth-century artists: paranoid consciousness. He then veers off into the territory of wife-helping-ailing-great-man (“It’s time for your pill, dear”), and in doing so misses a splendid opportunity.

After all, there aren’t too many directors out there who wouldn’t jump at the chance to tell a story about a paranoid schizophrenic genius living in the middle of the Red Scare, trapped in a fantasy world in which Russian spies and shadowy G-Men lurk around every corner. The spine-tingling beauty of highly localized point of view narration in films— “first person” narration is perhaps a better term, though somewhat inaccurate— is the opportunity for the director to trick an audience by blurring the real and the unreal until the audience is breathlessly— and joyfully— running through the maze of the film like white mice in a laboratory. David Cronenberg’s “Naked Lunch”, for example, or Darren Aronofsky’s “Pi” (about a similarly gifted mathematician) both succeed in evoking the wild labyrinth of paranoia and insanity that one might expect from Gogol or Nabokov. David Fincher had a blast with imaginary friends in “Fight Club”. And dear old Hitchcock took fiendish pleasure in telling stories about men who were, quite simply, losing their marbles.

Howard’s film, on the other hand, disappointingly substitutes a clinical prognosis for spellbinding excitement. In fact, there exist few films in movie history that waste their potential as sadly as “A Beautiful Mind”. The only question is, did Howard aggressively seek to rob his movie of its potential? “A Beautiful Mind”, in holding up the values of middle America as a necessary corrective to original and brilliant thinking, is really just another case of the mediocre taking revenge on the gifted. Howard may not understand higher thinking— Nash’s intellectual exertion shows up as a benign acid trip— but who cares about the cosmos when there are diapers to change? |

|