Vincent Gallo’s “The Brown Bunny” isn’t so much a good or bad film as a work of art that frustrates any judgment about it. Failing as a narrative film, it somehow also manages to avoid reaching the status of either high art or trash. There’s no payoff, just a trancelike procession of static imagery that has no compelling reason to exist. It is an art film made in the form of a museum piece, as if Gallo’s movie ought to be playing on a series of small TV screens as part of an art gallery photography exhibit, the story no more essential to the main showpiece than the headphones that provide information to gallery walkers. Vincent Gallo’s “The Brown Bunny” isn’t so much a good or bad film as a work of art that frustrates any judgment about it. Failing as a narrative film, it somehow also manages to avoid reaching the status of either high art or trash. There’s no payoff, just a trancelike procession of static imagery that has no compelling reason to exist. It is an art film made in the form of a museum piece, as if Gallo’s movie ought to be playing on a series of small TV screens as part of an art gallery photography exhibit, the story no more essential to the main showpiece than the headphones that provide information to gallery walkers.

But the movie is far too immobile and spacey for that. “The Brown Bunny” feels less like cinema than it does like slowly flipping through a good coffee table art book in slow motion. Gallo’s Bud Clay visits a rest-stop for a Coke in one scene and has an encounter with a woman there (played by a sandblasted Cheryl Tiegs). The scene goes on for much longer than it should. Gallo teases out the unspoken dialogue between the two lonely figures at the deserted stop until, at last, they give in to some precious subtext that seems borrowed from another movie.

The story leap is silly and uninteresting, but undeniably Gallo’s work with the camera fascinates. Here, as he does throughout the film, Gallo allows the camera to linger on the characters and their surroundings long enough for a quotidian lyricism to emerge: the click of Bud’s boots, the sun striking the lone van in the parking lot, the uncertainty and yearning of Tiegs’ body language, the blur and hum of distant freeway traffic. Scenes like this make “The Brown Bunny” watchable, at times even beautiful.

The now-infamous clips of Bud’s cross country trip, in which the audience is treated to long stretches of looking through the windshield at the midwestern landscape, are stirring if given half a chance to sink in. Gallo’s eye never wavers, his camera setups are never annoying and rarely arbitrary, as would be true of the selfishly indulgent director he’s accused of being. He has an understanding of lowbrow suburbia that verges on caricature with an eye for ways to mine its hidden truths. For instance, if Rose’s parents are distractingly amateurish—the woman looks as if she can’t act at all, while the man hilariously overacts in the corner of the frame—there is enormous pleasure in seeing the ugly vinyl chairbacks, the dirty sunlight leaking through the windows of the kitchen, the cheap tile, and the myriad knicknacks on the counter. Gallo doesn’t just show these details, he reveals them. Every scene rewards close observation.

Every poorly dramatized sequence is redeemed by that kind of detailed scene setting. Later, when Bud meets a prostitute in Las Vegas, refuses her come-on, then changes his mind and circles around the block to go and pick her up, the greatness of the scene is that Gallo never cuts away. The audience rides with Bud on the full circuit. Corner, blinker, alley, stop, blinker, corner, corner, back to prostitute. By not cutting away, Gallo imprints in our minds the agonized, impatient vacuum in Bud’s mind—time’s inexorable trampling of Bud’s little life—without making us feel that he is wasting our time.

Most viewers, like those at Cannes, apparently, will not accept that nuance. Certainly there’s a fine line between dead time for a character and dead time for the audience, but there’s an unusually bold push for realism in “The Brown Bunny” that should give Gallo a pass. The langourous, hypnotic rhythms, like the rush of the windshield wipers in a storm, partake of the best kind of realism, allowing us a second, more meditative look at the everyday.

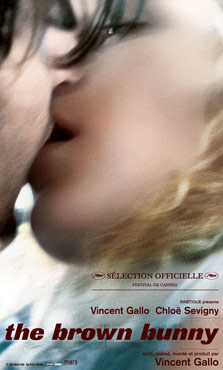

Unfortunately the all but plotless film suddenly drops Shakespearean melodrama in our laps. The ending of “The Brown Bunny” is notable not because of the infamous (and highly convincing) oral sex scene with Chloe Sevigny’s Daisy, which is boring and untitillating, but rather because it confirms that for the first two hours of the film Gallo has not been carefully charting the aforementioned emptiness of Bud’s life, but actually failed to evoke the conflict in the character. Suddenly, all that staring at the road turns out to have been a false front. This isn’t subtlety, it’s an underwritten story.

As soon as Bud’s pants drop the film is instantly vacated of whatever substance had accreted in its margins. This occurs even as Bud finally explodes in an excruciating scene that plays like “Othello” reimagined by a teenaged Dostoevsky who didn’t get a date to the Prom. While it’s hard to complain when those two hours have contained a slew of unforgettable images, it nevertheless makes you wish Gallo would have left out the cheap theatrics and made “The Brown Bunny” what it really wants to be—a coffee table book. |